Manchester Theatre News & Reviews

REVIEW - Dancing At Lughnasa immerses you in atmosphere, music, memory, and of course, dancing!

BOOK YOUR TICKETS HERE

BOOK YOUR TICKETS HERE

On Saturday, we were invited to the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester to see Dancing At Lughnasa. Read what our reviewer Karen Ryder had to say about this Brian Friel play...

Dancing at Lughnasa has been receiving favourable feedback following its run in Sheffield and has continued to do so in its opening week at The Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester, so I was looking forward to experiencing this Brian Friel semi-autobiographical play for myself. Upon entering the infamous ‘in the round’ theatre, the striking staging immediately transports you back to a moment in time, a snapshot of a memory as you enter a world remembered by Michael. A large family table assumes centre stage, with the outskirts fragmented into segments representative of the kitchen window, the working area, the garden, the lane, and even the height of a sycamore tree. Each area is adorned with enough dressing to feel real, without excess, reflecting the struggle this family endured. Two wooden posts supporting a washing line stood on the edge of the space, and as my seat fell behind one of these posts, my only gripe was that I did have some of my view obscured, particularly during Michaels opening speech when the washing hanging from it blocked him completely. Upon leaving the theatre, we did also spot a large section that was representative of a corn field beyond one of the lanes, but this was entirely obscured from our viewpoint, even though we had very good seats. However, it is clear that Francis O’ Connor has created a wonderfully suggestive and symbolic world for us to inhabit with enough to guide us, and space enough for us to imagine.

Dancing at Lughnasa is a story created from Michael’s memories of growing up in County Donegal, Ireland and sharing a house with his mother and four aunts. It focuses on one year, 1936 when several influential things happened. His legendary Uncle Jack returned home from a missionary in Uganda Africa, his estranged father made an appearance, and towards the end of the year, everything changed as the stability of his family home became fractured and fragmented. Michael perhaps recalls with a heady mixture of memory and imagination the happening of this time, and as his memory falters and jumps around the timeline, we too are whisked back and forth, trying to keep up with his story. The story goes nowhere yet travels everywhere in equal measures, creating a delicious slice of his childhood and the world that shaped him. In this sense, it is an interesting psychological viewpoint to assess the things Michael remembers and how those things have shaped him into the adult that now stands before us, partnering with his own memory in a dance he vaguely remembers the steps to. We see the love that surrounded him and the struggles the adults thought they were shielding him from. We see the duty and demanding roles expected of women unfold, be questioned, be ignored, and be challenged. We see the societal expectations of family, community and religion and the cost of living outside of them, for Christine as a mother out of wedlock, Jack for returning home with new religious views, and Rose for loving a married man. We see love in its many forms, a mother’s love, an aunts love, sibling love, religious love, forbidden love, unrequited love, and romantic love. It peeks behind the curtain of opposing faiths living side by side, through sibling love if not understanding, and the ironic similarities between Jack’s newfound religion and the Celtic Pagan festival of Lughnasadh, the harvest festival where possessions are to be revoked and sacrificed, and deals are to be made as celebrations take place during ceremonies.

Dance appears in the show in varus forms too. From the scene that stays in everyone’s memory as the sisters vent their frustrations, their guttural rejection of circumstance, their desire and longing for something else or something beyond their current existence. As Maggie howls with a raw animalistic release, and fiercely thrashes her frustrations out of her limbs, hard into the floor, each sister finds their way in through their own unique dance. It is wild, it is electric, it is alive with exposed relief and vulnerability, and as Kate joins in with her own fierce and angry version of Irish dancing, it brings humour but also sadness as the realisation hits that even in her most emotive moments, she still needs structure and rules to guide her. Other dancing involves more demure and tender moments between Gerry and Chris, and equally between Gerry and Aggie as we see the heat of love and romance blossom under very different circumstances, reflected through dance. There is the wonderful moment of dance to ‘Anything Goes’ ring out of the unreliable Wireless radio, a radio that always seems to be working in accordance with Michaels memories of this time, highlighting the undeniable relationship between memory and music. Indeed this is given food for thought in Michaels closing moments as he admits to not so much recalling conversations or the words that were said, but more an atmosphere, a feeling, a sense of what home was.

Directed by Elizabeth Newman, the cast of Dancing At Lughnasa, do an undeniable job of bringing us exceptional characters that you truly care about. Martha Dunlea is youthful and hopeful whilst carrying the brutal experience of life on her young shoulders as Christine. She is all too aware of the dangers of love, and tries to protect her sister Rose from them, whilst unable to fully stop believing in the promises from her sons father Gerry. She is sweet and makes the audience easily root for her. Siobhán O’ Kelly portrays Kate as a feisty and protective older sister who does her best to keep the family glued together. She is one for keeping spirits up but being true to herself and speaking out more freely than the others, often clashing with Kate regarding who they are over who they’re expected to be and behave as. Rachel O’ Connell gives us an infectiously enthusiastic Rose, who shows naivety that results in her not really being listened to or taken as seriously as the other sisters. Her emotions eventually overspill and result in some shocks, which are played out intriguingly as she somewhat withdraws, making the audience feel the same concern as the other sisters. Laura Pyper plays Agnes and lives a life of lies as she desperately tries to keep her feelings locked away out of sense of family duty. She demonstrates her particularly close bond to Rose with ease and we feel her pain as her sense of duty to the family and all that she does for them practically, is somewhat taken for granted. Natalie Radmall-Quirke is the final sister Kate, a more stern and precise sister, committed to worrying about outward appearances and societal expectations. A devout Catholic, she lives for routine, structure, and rules yet loves her family deeply, causing an anguished tension that she cannot resolve, and so depending on you own views, you may not agree with her position, but she plays it in such a gifted way, that we fully understand it and feel for her.

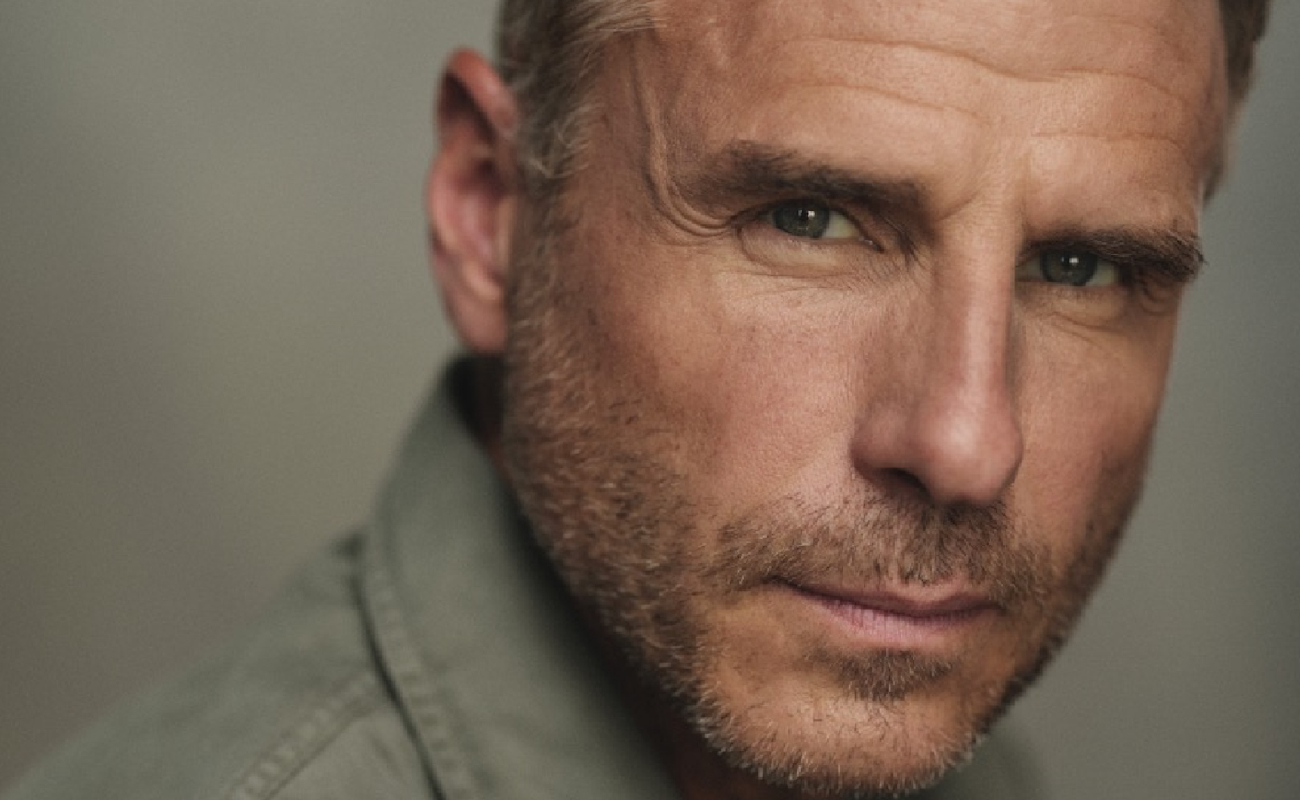

Kwaku Fortune as Michael pulls the show together with his interjections, memories, and conversations with his Aunts, as he is removed from being in the character of child Michael, instead hovering above it in his own timeline. It is a difficult concept and theatre technique, and one I enjoyed experiencing through this controlled performance. Frank Laverty as Jack takes his character on a transformative journey, from the confused, weakened man we first encounter, to one full of vigour, certainty, and conviction in his own faith, refusing to cower to expectation. Marcus Rutherford as Gerry is the antithesis of the sisters, floating through life with ease, ignoring his responsibilities with no guilt, coming and going as he pleases, and yet still making him likeable. He does a great job of enabling us to understand why, despite his ability to step up and support Christine and his son with his presence, two women are able to fall in love with him, for he is effortlessly charming.

Dancing At Lughnasa delivers fantastic performances, explores its own story as it goes and sits comfortably within its own skin. The idea of memory runs deep throughout, as does family, freedom, and love. Each of these elements provokes interesting discussion for they evoke such personal definition, providing a unique and individual viewing for every audience member. For me, the show was both funny and sad, nostalgic yet relevant, intimate yet removed. It was everything all at once, a paradox of its own existence, making it a difficult one to define or describe. It is a play full of unanswered questions, encouraging it to stay with you long after the actors have bid you goodbye. Dancing At Lughnasa raises questions about what religious beliefs look like, can they change yet be rooted in the same audacious love? It raises questions of faith, trust, and the fine line it walks if your opinions differ to someone else. It questions the strength and accuracy of memory and if that is a good or bad thing, and it makes us question what it means to live versus what it means to be alive. And of course, it questions what dance means to each of us, from release to seduction, self-expression to belonging to a community, a means of communication both in the here and now and as memory. So make your way down to The Royal Exchange to be immersed in atmosphere, music, memory, and of course, dancing.

WE SCORE DANCING AT LUGHNASA...

WATCH OUR "IN CONVERSATION WITH KWAKU FORTUNE" VIDEO DISCUSSING THE SHOW

Dancing At Lughnasa is on at The Royal Exchange until 8th November.